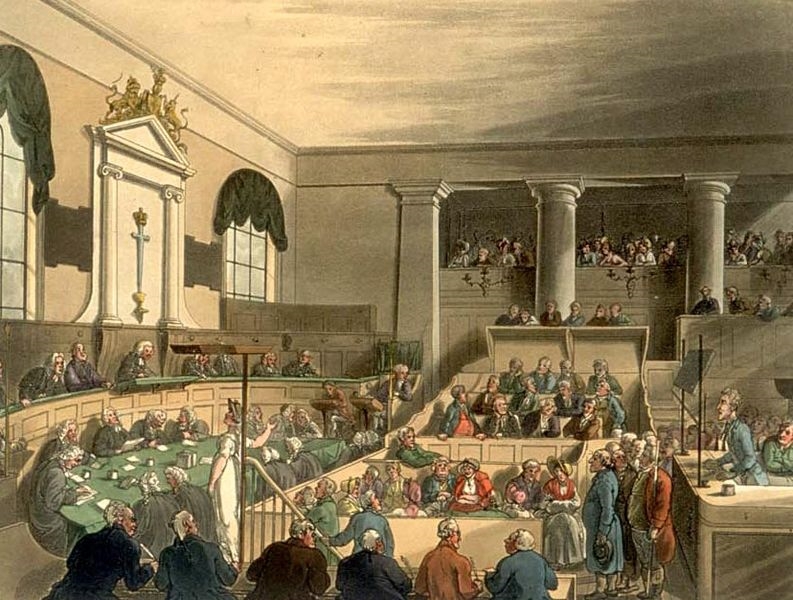

The court-house contains, besides ample accomodation for the judges, alder men, common-councilmen, sheriffs, and under-sheriffs, two large courts, called the Old Court and New Court, and two or three secondary courts, which are only used when the pressure of business is rather heavy. The gravest offences are usually tried in the Old Court on the Wednesday or Thursday after the commencement of the session, on which days one or two of the judges from Westminster sit at the Old Bailey. The arrangement of the Old Court may be taken as a tolerably fair sample of a criminal court. The bench occupies one side of the court, and the dock faces it. On the right side of the bench are the jury-box and witness-box; on the left are the seats for privileged witnesses and visitors, and also for the reporters and jurymen in waiting. The space bounded by the bench on one side, the dock on another, the jury-box on a third, and the reporters box on the fourth, is occupied by counsel and attorneys, the larger half being assigned to the counsel.

Over the dock is the public gallery, to which admission was formerly obtained by payment of a fee to the warder. It is now free to about thirty of the public at large at one time, who can see nothing of the prisoner except his scalp, and hear very little of what is going on.

The form in which a criminal trial is conducted is briefly as follows: The case is submitted to the grand jury, and if, on examination of one or more of the witnesses for the prosecution, they find a prima facie case against the prisoner, a "true bill" is found, and handed to the clerk of arraigns in open court. The prisoner is then called upon to plead: and, in the event of his pleading "guilty," the facts of the case are briefly stated by counsel, together with a statement of a previous conviction, if the prisoner is an old offender, and the judge passes sentence. If the prisoner pleads "not guilty," the trial proceeds in the following form. The indictment and plea are both read over to the jury by the clerk of arraigns, and they are charged by him to try whether the prisoner is "guilty" or "not guilty." The counsel for the prosecution then opens the case briefly or at length, as its nature may suggest, and then proceeds to call witnesses for the prosecution.

At the close of the "examination in chief" of each witness, the counsel for the defence (or, in the absence of counsel for the defence, the prisoner himself) cross-examines. At the conclusion of the examination and cross-examination of the witnesses for the prosecution, the counsel for the prosecution has the privilege of summing up the arguments that support his case. If witnesses are called for the defence, the defending counsel has, also, a right to sum up; and in that case the counsel for the prosecution has a right of reply. The matter is then left in the hands of the judge, who "sums up," placing the facts of the case clearly and impartially before the jury, pointing out discrepancies in the evidence, clearing the case of all superfluous matter, and directing them in all the points of law that arise in the case.

The jury then consider their verdict, and, when they are agreed, give it in open court, and the prisoner at the bar is asked whether he has anything to say why the sentence of law shall not be passed upon him. This question is little more than a matter of form, and the judge rarely waits for an answer, but proceeds immediately to pass sentence on the prisoner.

A visitor at the Old Bailey, to whom the courts of Westminster or Guildhall are familiar, will probably be very much struck with the difference between the manner in which the Nisi Prius and the criminal barristers are treated by the officials of their respective Courts. At Westminster the ushers, who are most unpleasant in their demeanour towards the public at large, are as deferential in their tone to the bar as so many club servants. Like Kathleen's cow, though vicious to others, they are gentle to them. Indeed, at Westminster the bar are treated by all the officials as gentlemen of position have a right to expect to be. But at the Old Bailey it is otherwise. They appear to be on familiar terms with criers, ushers, thieves' attorneys, clerks, and police serjeants. Attorneys' clerks, of Israelitish aspect, buttonhole them; bumptious criers elbow them right and left, and the policemen on duty at the bar-entrance chaffs them with haughty condescension.

Of course there are many gentlemen at the criminal bar whose professional position overawes even this overbearing functionary; but it unfortunately happens that there are a great many needy and unscrupulous practitioners at the Old Bailey, who find it to their advantage to adopt a conciliatory policy towards everybody in office; for it is an unfortunate fact, that almost everybody in office has it in his power, directly or indirectly, to do an Old Bailey barrister a good turn. "Dockers," or briefs handed directly from the prisoner in the dock to counsel, without the expensive intervention of an attorney, are distributed pretty well at the discretion of the warder in the dock, or of the gaoler to whose custody the prisoner has been entrusted since his committal; and there are a few needy barristers who are not ashamed to allow their clerks to tout among prisoners' friends for briefs at half fees. It is only fair to state, that the counsel who resort to these ungentlemanly dodges form but a small proportion of the barristers who practise at the Old Bailey; but still they are sufficiently numerous to affect most seriously the tone that is adopted by Old Bailey officials towards the bar as a body.

The conventional Old Bailey barrister, however, is a type that is gradually dying out. The rising men at the criminal bar are certainly far from being all that could be desired; but their tone, in cross-examination, is more gentlemanly than that commonly in vogue among Old Bailey barristers of twenty years since. There are a few among them who occasionally attempt to bully, not only the witnesses, but even the judge and jury; but they always get the worst of it. As a rule, cross-examinations are conducted more fairly than they were, and a determination to convict at any price is rarer on the part of a prosecuting counsel than of yore. If some means could be adopted to clear the court of the touting counsel, or, at all events, to render their discreditable tactics inoperative, a great change for the better would be effected in the tone adopted towards the bar by the officials about the court. As it is, it is almost impossible for a young counsel to retain his self-respect in the face of the annoying familiarities of the underlings with whom he is brought into contact. On the occasion of our last visit to the Old Bailey, during the trial of Jeffrey for the murder of his son, we happened to witness a dispute between an insolent policeman, stationed at the bar-entrance, and a young barrister in robes, who was evidently not an habitue of that court.

The barrister had a friend with him, and he wanted to get a place for his friend, either in the bar seats, or in the seats set aside for the friends of the bench and bar. The policeman in question placed his arm across the door, and absolutely refused to allow either the barrister or his friend to enter, on the ground that the court was quite full. The barrister sent his card to the under-sheriff, who immediately gave directions that both were to be admitted to the bar-seats, which were occupied by about a fourth of the number which they would conveniently accomodate, about half the people occupying them being friends of counsel who, we suppose, were on more intimate terms with the discourteous functionary than was the barrister in question. On another occasion it came to our knowledge that a barrister, who did not habitually practise at the Old Bailey, was refused admission at the bar entrance to the court-house by the police-sergeant stationed there. He showed his card, but without avail, and eventually he expressed his intention of forcing his way past the policeman, and told that official that if he stopped him he would do so at his peril.

The policeman allowed him to pass, but actually told another constable to follow him to the robing-room, to see whether he had any right there or not. The barrister, naturally annoyed at being thus conveyed in custody through the building, complained to one of the under-sheriffs for the time being, but without obtaining the slightest redress. Of course this system of impertinence has the effect of confining Old Bailey practice to a thick-skinned few; but it does not tend to elevate the tone of the bar (of which the Old Bailey barrister is unfortunately generally taken as a type); and those who are jealous for the honour of the profession should take steps to do away with it.

To a stranger, a criminal trial is always an interesting sight. If the prisoner happens to be charged with a crime of magnitude, he has become quite a public character by the time he enters the dock to take his trial; and it is always interesting to see how far a public character corresponds with the ideal which we have formed of him. Then his demeanour in the dock, influenced, as it often is, by the fluctuating character of the evidence for and against him, possesses a grim interest for the unaccustomed spectator.

He is witnessing a real sensation drama, and as the case draws to a close, if the evidence has been very conflicting, he feels an interest in the issue akin to that with which a sporting man would take in the running of a great race. Then the deliberations of the jury on their verdict, the sharp, anxious look which the prisoner casts ever and anon towards them, the deep breath that he draws as the jury resume their places, the trembling anxiety, or, more affecting still, the preternaturally compressed lips and contracted brow, with which he awaits the publication of their verdict, and his great, deep sigh of relief when he knows the worst, must possess a painful interest for all but those whom familiarity with such scenes has hardened. Then comes the sentence, followed, perhaps, by a woman's shriek from the gallery, and all is over, as far as the spectator is concerned. The next case is called on, and new facts and new faces soon obliterate any painful effect which the trial may have had upon his mind.

Probably the first impression on the mind of a man who visits the Old Bailey for the first time is that he never saw so many ugly people collected in any one place before. The judges are not handsome men, as a rule, the aldermen on the bench never are; barristers, especially Old Bailey barristers, are the ugliest of professional men, excepting always solicitors; the jury have a bull-headed look about them that suggests that they have been designedly selected from the most stupid of their class; the reporters are usually dirty, and of evil savour; the understrappers have a bloated, overfed, Bumble-like look about them, which is always a particularly annoying thing to a sensitive mind; and the prisoner, of course, looks (whether guilty or innocent) the most ruffianly of mankind, for he stands in the dock. We remember seeing a man tried for burglary some time since, and we came to the conclusion that he had the most villanous face with which a man could be cursed.

The case against him rested on the testimony of as nice-looking and ingenious a lad as ever stepped into a witness-box. But, unfortunately for the ingenious lad, a clear alibi was established, the prisoner was immediately acquitted, and the nice boy, his accuser, was trotted into the dock on a charge of perjury. The principal witness against him was the former prisoner, and we were perfectly astounded at the false estimate we had formed of their respective physiognomies. The former prisoner's face was, we found, homely enough; but it absolutely beamed with honest enthusiasm in the cause of justice, while the nice lad's countenance turned out to be the very type of sly, insidious rascality. It is astonishing how the atmosphere of the dock inverts the countenance of any one who may happen to be in it. And this leads us to the consideration how surpassingly beautiful must that ballet-girl have been, who, even in the dock, exercised so extraordinary a fascination over a learned deputy-judge at the Middlesex sessions not long ago.

We remember once to have heard a well-known counsel, who was defending a singularly ill-favoured prisoner, say to the jury, "Gentlemen, you must not allow yourselves to be carried away by any effect which the prisoner's appearance may have upon you. Remember, he is in the dock; and I will undertake to say, that if my lord were to be taken from the bench upon which he is sitting, and placed where the prisoner is now standing, you, who are unaccustomed to criminal trials, would find, even in his lordship's face, indications of crime which you would look for in vain in any other situation!" In fairness we withhold the learned judge's name.

Perhaps the most ill-favoured among this ill-favoured gathering are to be found among the thieves' attorneys. There are some Old Bailey attorneys who are respectable men, and it often happens that a highly-respectable solicitor has occasion to pay an exceptional visit to this establishment, just as queen's counsel standing at Nisi Prius are often employed in cases of grave importance; but these solicitors of standing are the exception, and the dirty, cunning-looking, hook-nosed, unsavoury little Jews, with thick gold rings on their stubby fingers, and crisp black hair curling down their backs, the rule. They are the embodiment of meat, drink, washing, and professional reputation to the needy barristers whom they employ, and, as such, their intimacy is, of course, much courted and in great request. Of course many Old Bailey barristers are utterly independent of this ill-favoured race; but there are, unfortunately, too many men to be found whose only road to professional success lies in the good-will of these gentry. There are, among the thieves' lawyers, men of acute intelligence and honourable repute, and who do their work extremely well; but the majority of them are sneaking, underhand, grovelling practitioners, who are utterly unrecognized by men of good standing.

W.S.Gilbert , London Characters and the Humorous Side of London Life, 1870?

Victorian London - Publications - History - The Queen's London : a Pictorial and Descriptive Record of the Streets, Buildings, Parks and Scenery of the Great Metropolis, 1896 - Interior of the Central Criminal Court

-Vol.1-] Just imagine ourselves in Robert Jillett’s shoes!

[-107-]

A TRIAL AT THE OLD BAILEY

By GEORGE R. SIMS

The Old Bailey is the Central Criminal Court of London, and here the last scenes of most of the great criminal tragedies of the capital are enacted. In the close atmosphere of a small, inconvenient, and utterly inadequate chamber the most famous advocates of the past and of the present have contended for the life of a fellow creature.

Passing the grim, forbidding prison of Newgate, with its allegorical chains, and its black memories of the days when a public execution brought together a ribald mob composed of the dregs of the populace, we find immediately adjoining it the Old Bailey. Outside a large crowd is already assembled, for this, it is anticipated, will be the last day of the trial of a young murderer, whose cool, calculating crime has sent a thrill of horror through the kingdom.

We are early, but if we attempt to enter at the principal doorway we shall have to return. For the trial at which we wish to assist every place has been allotted and admission is by the Under-Sheriff's signed order only. To reach the Court comfortably we shall therefore enter by the side gate. We are provided with the necessary card, and, showing this, the police on duty step aside and permit us to pass. We find ourselves in the courtyard. Here already stands the prison van known as "Black Maria." From it the prisoners who have been brought from another gaol are alighting to be led to the cells in which they will be detained until it is time for them to be placed in the dock.

In the covered yard, in which we wait until the officer at the foot of the stairs leading to the Court has time to inspect our card of admission, there is a wooden bench. On this are seated two pale-faced, nervous looking women, and an old, grey-hair man. One of the women, the younger, is the sweet-heart of the man at whose trial we are to assist. The old gentleman is his grandfather. Close by, talking together in a low tone, are a group of witnesses.

Presently the Sheriff's servant in livery [-108-] comes to the top of the stairs, and we send our card to him. He reads it, and beckons us to follow him. We pass through a glass door at the top of the stairs, and find ourselves in a narrow passage filled with barristers and officials.

A wooden barrier near the entrance of the court is raised for us, and the door-keeper ushers us into a seat in the well. We have only time to glance round the crowded chamber when the cry of the Usher is heard, and everybody starts to his feet. Preceded by the City officials and the Lord Mayor, the Lord Chief Justice enters and takes his seat.

The prisoner comes up the stairs accompanied by two warders, and steps down to the front of the dock. One of the warders puts a chair for him, and he sits down. His face is pale, and though throughout the week the trial has lasted he has borne himself with considerable bravado, he shows nervousness to-day. For it is Saturday, and he has heard the Judge say that he will sit to any hour in order that the verdict may be reached without the intervention of a Sunday. To-day is, therefore, to seal the prisoner's fate, and he knows that before many hours are over he will leave the Court a free man or be taken to the condemned cell, there to wait until he is led out to die a shameful death.

The Counsel for the defence, before making his speech, which it is understood will be a short one, has promised to call a witness who was not able to be present before. In the course of the evidence it is necessary that a large photograph of the murdered woman should be handed to the witness and to the Jury. This photograph is held by the Counsel in such a way that the prisoner in the dock cannot help seeing it. He looks at it almost carelessly. There is not a soul in Court who doubts the man's guilt, and this careless look makes people turn to each other and whisper. How can a man standing in the shadow of death look upon the face of his victim without a flushing of the cheeks, without a tremor of the lips? A moment later, and the jacket that the poor woman wore on the night of the crime is held up. The prisoners looks at it for a moment, then glances out of the window, and becomes apparently interested in two sparrows who are chirruping on the wall. The nervousness he betrayed when he stepped into the dock he has apparently conquered.

Counsel makes his speech. It is a clear impassioned effort to belittle the evidence as purely circumstantial, and to build up a theory that the murder was committed by a man unknown who has been vaguely hinted at as having been seen in the neighbourhood of the crime. In the course of the speech there is a strong attack made upon the police who have had "the getting up of the case." The detectives to whom unpleasant reference is made are seated near the solicitors' table. One of them holds on his knee the black bag which contains the direct evidence that connects the prisoner with the deed. Counsel points a denunciatory finger at him, and refers to him in terms of withering scorn. But the detective sits unmoved, with the blank expression on his face of a deaf man in church during sermon time.

The Judge makes an occasional note or two, then sits back in his seat and folds his hands in his lap. But the prisoner's face relaxes into a grim smile when the police who have hunted him down are abused, and in the glance he darts at the victim of his Counsel's scathing eloquence there is a world of malignity.

It is a brilliant speech, and the rumour that it is stirring and dramatic has spread to the other Courts. Barristers look in, and occupy a tightly packed space between the press box and the public seats. From the gallery above the spectators lean over, listening intently. On the bench a well-known peer, a famous general, and a clergyman have taken their places and are deeply interested. Packed tightly together in the limited space allotted to the public are politicians, literary men, dramatists, actors, men of fashion and of finance. The Jury listen attentively, but with impassive faces. The foreman, half turned towards the Counsel, leans his elbow on the edge of the jury box and rests his head upon his hand.

The speech as it progresses and becomes more and more dramatic and impassioned has a distinct effect upon the prisoner. It is raising his hopes. The same thought has come into his mind that has come into the minds of the large audience - Will the Jury seize the loophole offered them by the advocate and give the prisoner the benefit [-110-] of the doubt. The advocate finishes with a magnificent burst of eloquence. As he utters the last word and sinks into his seat one is almost tempted to applaud him. It seems a drop from the clouds to the earth when the Judge, glancing at the clock, says, "I think this will be a convenient time to adjourn."

Everybody rises. The Lord Mayor, the Aldermen and others on the bench, stand back as the Lord Chief Justice walks with quiet dignity to the door where Mr. Under-Sheriff is waiting to conduct him to the luncheon room. The warders turn to the prisoner, who rises, glances at the clock, and then goes down the little staircase that leads to the cell below, in which his mid-day meal will be served.

The prisoner can order practically what he likes, with certain restrictions as regards liquor. His lunch is sent in from a neighbouring hostelry, and he eats it under fairly comfortable circumstances.

The Court now rapidly empties. The barristers go to their luncheon room, and the spectators file out into the street to take their refreshment. There is a luncheon bar at the public house opposite the Old Bailey, and her the prospects of the verdict are eagerly discussed.

In response to the courteous invitation of the Under-Sheriff, we are privileged to be his guests. We find ourselves in a comfortable dining room in which a big table is laid for luncheon. The Lord Chief in his robs sits at the head of it. Here and there along the table are barristers and distinguished visitors to whom the Under-Sheriff has extended his hospitality. Liveried servants wait upon the guests, who speak together in a low tone. In the presence of the Lord Chief no reference is made aloud to the case that is being tried.

After luncheon the Lord Chief retires, and coffee is served in an adjoining apartment. Here one meets barristers and visitors who have been lunching in other rooms. Here is the clergyman who has been sitting quietly on the bench all the morning. It is only when we learn who he is that the significance of his presence is understood. He is the Sheriff's Chaplain. In the event of the verdict being against the prisoner he will be called upon to take an active part in the later proceedings.

Suddenly there is a general murmur. The [-111-] word has gone round that the Lord Chief is ready to resume. The Under-Sheriff is quickly in attendance, and precedes his Lordship to the Court. There is a moment's pause while barristers and spectators settle down, and then the prisoner is brought up and the trial proceeds.

The Counsel for the prosecution rises. He is about to reply on the whole case. The prisoner leans forward and listens attentively to the opening. Slowly, but with masterly precision, the eminent King's Counsel, who is acting for the Treasury, sweeps away point after point made by the defence. With perfect fairness, but with deadly effect, he reweaves the evidence, twisting the separate strands into a hangman's rope. The prisoner shifts uneasily in his chair. He can no longer conceal his nervous apprehension. His lips twitch. There is a flushing of the neck and cheeks. Again and again he passes his handkerchief over his face. For the first time a warder has seated himself close behind him, and another warder has taken the vacant corner.

As Counsel drives nail after nail into the coffin of a living man, the prisoner, whose head has been bending down, sways slightly, and the warder nearest him catches his arm. But for that grasp he would probably have fainted. He recovers himself, but the warders' shoulders now almost touch his.

For two hours the Counsel for the Crown speaks, always in the same calm but convincing manner. When at last the speech is ended, there is but one opinion in Court. The prisoner is doomed. Only were and there men whisper to each other there is a rumour that one Juryman is against capital punishment. He may hold out and delay the verdict.

But the Lord Chief has yet to sum up. As he begins to speak the prisoner revives a little. For the summing up is to the speech of Cousel as a gentle, purling brook after the remorseless flood. The Judge brings before the Jury all that should weigh with them in the prisoner's favour, all that should tell against him. It is a quiet, almost a soothing summing up, but it disposes of all possible doubt in the minds of the audience. Nothing but an obstinate Juryman can save the prisoner now.

It is past six o'clock when the Judge withdraws, and the Clerk, giving the Jury into custody of the Usher, bids them retire and consider their verdict.

Again the Judge leaves the bench, and the prisoner is led below. The Jury file out, and the spectators eagerly scan their faces as they go. Which is the Juryman who is expected to be obstinate and to keep us all in a state of suspense for hours?

With the departure of the Jury a buzz of [-112-] conversation begins. Counsel come forward and chat with the spectators whom they know. Journalists who have to get their "special" accounts done for the Sunday papers look anxiously at their watches. It is past six - it may be eight before the Jury returns, it may be nine. Will there be time for dinner? Will it be safe to go to a restaurant? It is impossible to say. The Jury may agree in a few minutes if the verdict is to be guilty; they may remain deliberating for hours if only one of their number is in favour of an acquittal.

The atmosphere of the Court has become almost unbearable with the night. The gas jets have all been lighted long ago, and the air of the small chamber, which has been breathed for more than ten hours by a packed audience, has become heavy and vitiated. The faces of the audience are anxious and flushed. The excitement and suspense are intensified by the sense of the impending doom of a fellow-creature. Outside in the corridor they tell us that the young man's sweetheart is in a room waiting for the verdict. His father and mother have left the building, unable to bear the strain.

The clock ticks on - the Jury have been gone half an hour. Have they disagreed? Must we remain in this terrible Court to hear sentence pronounced at midnight, as happened years ago in the trial of two men and two women for the Penge murder?

Just as the spectators have made up their mind that the verdict may be delayed for hours, there is a sudden excitement near the door by which the Jury retired. The Usher has come to say they are agreed upon their verdict. Instantly a dead silence falls upon the Court. Everyone returns to his seat. Counsel take their places. The Judge enters slowly and solemnly.

Now for the first time we can see that the prisoner is in readiness. We catch sight of him half way up the steps that lead to the dock. There are two warders with him, and an officer in plain clothes stands behind him. The Judge takes his seat. A warder touches the prisoner on the shoulder, he mounts the remaining steps and comes down to the front of the dock. Two warders stand by him on each side.

The Jury re-enter. The Clerk calls out their names one by one, and they answer to them. Then he says to them:

"Gentlemen of the Jury, have you agreed upon your verdict?"

The Foreman answers, "Yes."

"Do you find the prisoner at the bar guilty or not guilty?"

There is a moment's hush, a general catching of the breath.

"Guilty."

The warders' hands almost join behind the prisoner's back.

But he has only given a little start. For a moment his jaw has fallen, but he closes it again with a snap and stands pale - almost defiant.

He is asked the usual question - Has he anything to say why sentence should not be passed upon him?

In a husky voice he replies,

"Only that I am innocent, sir."

The Judge's Clerk has risen from his desk. He has something in his hand. It is a square piece of cloth. It is the Black Cap. He lays it on the Judge's wig, and then for the first time we realise that the clergyman who has [-113-] been present all day on the bench has put on a black gown and stands near the Judge.

The Lord Chief addresses the prisoner by name. Only a few words he speaks to him, saying that he will not harrow his feelings. Then he pronounces the dread sentence of the law. When he says "And may the Lord have mercy on your soul," over the solemn silence that follows rings the deep voice of the chaplain -

"Amen!"

No one moves for a second, everyone is watching the condemned man. He lingers for a second, his lips moving as though he wanted to speak. Then the warders take his arms. He turns, and, with a last look around the Court as though in search of someone, he disappears from view.

The Court rises. The spectators come into the corridors. There is a hum of conversation, a hurried exchange of good nights, and we pour out into the welcome air of the street.

Outside there is a crowd. They heard the news some minutes ago. The Judge had barely passed the sentence when we caught a fair cheer. Now, as we get outside, where the police are busy keep a pathway for us, we are questioned on all sides as to how the prisoner behaved at the finish.

Before we have reached the end of the street of doom the newsboys are rushing up. One of them stands in front of the Old Bailey with papers on his arm and a contents bill open in front of him. On it we see, in large letters,

VERDICT

The boy begins to shout the news. The gates of court-yard open and a four-wheeled cab comes slowly out.

In it are two women. One is lying with her head upon the other's shoulder. The fainting woman is the sweetheart of the man who death sentence is being shouted almost in her ears as the cab passes down Newgate Street.

For so many prisoners a trial such as this was the precluder to their leaving for Australia.

Victorian London - Legal System - Courts - Old Bailey

Curiosity has occasionally led us into both Courts at the Old Bailey. Nothing is so likely to strike the person who enters them for the first time, as the calm indifference with which the proceedings are conducted; every trial seems a mere matter of business. There is a great deal of form, but no compassion; considerable interest, but no sympathy. Take the Old Court for example. There sit the judges, with whose great dignity everybody is acquainted, and of whom therefore we need say no more. Then, there is the Lord Mayor in the centre, looking as cool as a Lord Mayor CAN look, with an immense BOUQUET before him, and habited in all the splendour of his office. Then, there are the Sheriffs, who are almost as dignified as the Lord Mayor himself; and the Barristers, who are quite dignified enough in their own opinion; and the spectators, who having paid for their admission, look upon the whole scene as if it were got up especially for their amusement. Look upon the whole group in the body of the Court - some wholly engrossed in the morning papers, others carelessly conversing in low whispers, and others, again, quietly dozing away an hour - and you can scarcely believe that the result of the trial is a matter of life or death to one wretched being present. But turn your eyes to the dock; watch the prisoner attentively for a few moments; and the fact is before you, in all its painful reality. Mark how restlessly he has been engaged for the last ten minutes, in forming all sorts of fantastic figures with the herbs which are strewed upon the ledge before him; observe the ashy paleness of his face when a particular witness appears, and how he changes his position and wipes his clammy forehead, and feverish hands, when the case for the prosecution is closed, as if it were a relief to him to feel that the jury knew the worst. The defence is concluded; the judge proceeds to sum up the evidence; and the prisoner watches the countenances of the jury, as a dying man, clinging to life to the very last, vainly looks in the face of his physician for a slight ray of hope. They turn round to consult; you can almost hear the man s heart beat, as he bites the stalk of rosemary, with a desperate effort to appear composed.

They resume their places - a dead silence prevails as the foreman delivers in the verdict - Guilty! A shriek bursts from a female in the gallery; the prisoner casts one look at the quarter from whence the noise proceeded; and is immediately hurried from the dock by the gaoler. The clerk directs one of the officers of the Court to take the woman out, and fresh business is proceeded with, as if nothing had occurred.

No imaginary contrast to a case like this, could be as complete as that which is constantly presented in the New Court, the gravity of which is frequently disturbed in no small degree, by the cunning and pertinacity of juvenile offenders. A boy of thirteen is tried, say for picking the pocket of some subject of her Majesty, and the offence is about as clearly proved as an offence can be. He is called upon for his defence, and contents himself with a little declamation about the jurymen and his country - asserts that all the witnesses have committed perjury, and hints that the police force generally have entered into a conspiracy again him. However probable this statement may be, it fails to convince the Court, and some such scene as the following then takes place:

COURT: Have you any witnesses to speak to your character, boy?

BOY: Yes, my Lord; fifteen gen lm n is a vaten outside, and vos a vaten all day yesterday, vich they told me the night afore my trial vos a comin on.

COURT. Inquire for these witnesses.

Here, a stout beadle runs out, and vociferates for the witnesses at the very top of his voice; for you hear his cry grow fainter and fainter as he descends the steps into the court-yard below. After an absence of five minutes, he returns, very warm and hoarse, and informs the Court of what it knew perfectly well before - namely, that there are no such witnesses in attendance. Hereupon, the boy sets up a most awful howling; screws the lower part of the palms of his hands into the corners of his eyes; and endeavours to look the picture of injured innocence. The jury at once find him guilty, and his endeavours to squeeze out a tear or two are redoubled. The governor of the gaol then states, in reply to an inquiry from the bench, that the prisoner has been under his care twice before. This the urchin resolutely denies in some such terms as - S elp me, gen lm n, I never vos in trouble afore - indeed, my Lord, I never vos. It s all a howen to my having a twin brother, vich has wrongfully got into trouble, and vich is so exactly like me, that no vun ever knows the difference atween us.

This representation, like the defence, fails in producing the desired effect, and the boy is sentenced, perhaps, to seven years transportation. Finding it impossible to excite compassion, he gives vent to his feelings in an imprecation bearing reference to the eyes of old big vig! and as he declines to take the trouble of walking from the dock, is forthwith carried out, congratulating himself on having succeeded in giving everybody as much trouble as possible.

Charles Dickens, Sketches by Boz, 1836

The Old Bailey! Ugly words---associated (in a Londoners mind, at all events) with greasy squalor, crime of every description, a cold, bleak-looking prison, with an awful little iron door, three feet or so from the ground, trial by jury, black caps, bullying counsel, a "visibly affected" judge, prevaricating witnesses, and a miserable, trembling, damp prisoner in the dock. The Old Bailey---or rather the Central Criminal Court, held at the Old Bailey---is, par excellence, the criminal court of the country. In it all the excellences and all the disadvantages of our criminal procedures are developed to an extraordinary degree. The Old Bailey juries are at once more clearsighted and more pig-headed than any country jury.

The local judges---that is to say, the Recorder and the Common-Serjeant---are more logical, and more inflexible, and better lawyers than the corresponding dignitaries in any of our session towns. The counsel are keener in their conduct of defences than are the majority of circuit and session counsel; and at the same time the tone of their cross-examinations is not so gentlemanly, and altogether they are less scrupulous in their method of conducting the cases entrusted to them. The witnesses are more intelligent and less trustworthy than country witnesses. The officers of the court keep silence more efficiently, and at the same time are more offensive in their general deportment than the officers of any other court in the kingdom. And lastly, the degree of the prisoners guilt seems to take a wider scope than it does in cases tried on circuit. More innocent men are charged with crime and more guilty men escape at the Old Bailey than at any other court in the kingdom; because the juries, being Londoners, are more accustomed to look upon the niceties of evidence from a legal point of view, and in many cases come into the jury-box with exaggerated views of what constitutes a reasonable doubt, and so are disposed to give a verdict for the prisoner, when a country jury would convict.

The Old Bailey, although extremely inconvenient, is beautifully compact. You can be detained there between the time of your committal and your trial---you can be tried there, sentenced there, condemned-celled there, and comfortably hanged and buried there, without having to leave the building, except for the purpose of going on to the scaffold. Indeed, recent legislation has removed even this exception, and now there is no occasion to go outside the four walls of the building at all---the thing is done in the paved yard that separates the court-house from the prison. It is as though you were tried in the drawing-room, confined in the scullery, and hanged in the back garden.

Our picture shows the interior of the chief of the two Courts at the Old Bailey, where criminal trial for London and Middlesex are held. To the left is the dock; below the double windows is the jury box ; in the foreground, to the right, marked by the gas-pipe, is the reporters' box, in front of which are the seats for barristers ; while the small table in the well of the Court ie reserved for solicitors. Under the canopy, where hangs the emblematic sword of justice, the Lord Mayor, or the senior alderman no duty, takes his seat, with the judge at the unpretentious desk to his right, and with City colleagues and the Sheriff to his left. One of the judges from the Queen's Bench presides over the more important trials, instead of, as ordinarily, the Recorder or the Common Sergeant.